Fighting gangs from New York City in the 1950s used so many different weapons, and for the first part of this article I want to zero in on zip guns, a weapon that every gang owned at least one of, and sometimes more. This article will end with a short story of a Lower East Side youth who had an overpowering fascination with guns.

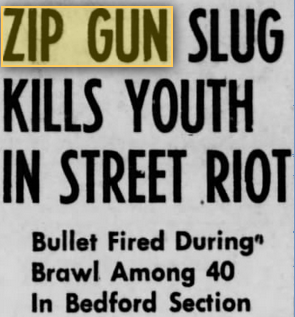

Often times gang members were too poor to buy a hand gun so they used their ingenious know-how in constructing home-made guns out of rubber bands, a coat hanger and a car aerial. Sometimes zip guns were constructed from toy pistols bought or stolen from department stores. One person explained that he made his from a toy derringer, a section of car antenna, a screw through a hole drilled in the hammer, and piano wire wrapped tightly around it all to keep it from exploding. The guns themselves were extremely inaccurate, and couldn’t be counted on unless in very close quarters. Despite their inaccuracy, they were still dangerous and I was able to find a couple of times where a zip gun actually killed someone.

Zip guns were possibly more dangerous to the operator than the one being shot at. Sometimes the gun exploded in the shooter’s hand or it backfired, blinding the shooter. One person I spoke to personally bandaged four zip gun bullet wounds. He recalled that “in one case when the gun was fired, the shell ejected back into the hand of the shooter and damaged his thumb.” The second time the “rubber band powered bolt was being pulled back into firing position [and] it released accidentally, firing the bullet into the gang member’s thigh.” The bullet passed entirely through so the entry and exit point were bandaged. In another identical incident, the gun fired as .22 caliber bird shot was being loaded. It lodged into the stomach of another gang member across from him. Alcohol was applied to the many wounds, and fortunately no serious damage was done. Even though they were notorious for being inaccurate and dangerous, gangs still packed zip guns in their fights and ambushes.

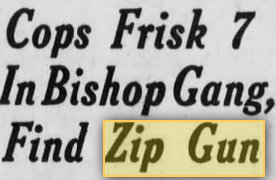

Some boys were very adept at making zip guns, even making them under the very noses of their teachers in shop class at school. The guns could shoot .22 caliber bullets, although nails and pins could also be used as ammunition. The New York Times had an article on two brothers who were caught selling zip guns to a Bronx gang called the Bronx Sportsmen. At the moment of their arrest, the brothers admitted they were in the process of filling an order for twelve zip guns. Another boy they had sold a zip gun to – and who led the police to the gunsmith brothers – admitted to the police that he was intending to use the gun to kill a rival member of a gang. Unfortunately the article did not report how much they were planning on selling each gun for.

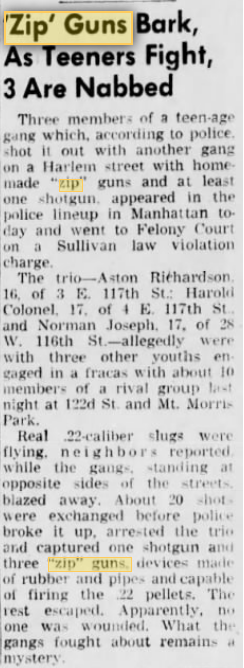

Obtaining ammunition for a zip gun was difficult but not impossible. If the person looking to buy the ammo looked old enough, bullets could be purchased at a sporting goods store, or, if that didn’t work, at amusement-arcade shooting galleries. One member from a Manhattan Upper East Side gang explained how he was able to get .22 caliber bullets at a shooting arcade without anybody noticing:

“Getting bullets is the tough part. Nobody’ll sell you no bullets. How’d I latch on to them? Man, I’ll tell you. You know them shooting galleries around Forty-second Street. Okay, you hang around until the dive is really hopping. Then you step up and hand out the bread for a couple of clips. Sure you have to shoot ‘em but if you’re hip, you fire real fast and slip a couple .22’s into your mit. Sometimes, if you play it cool, you can get away with a whole clip.”

And now a brief profile on someone who was fixated with guns; this story paints an interesting picture on an individual basis…

——

Charles B. was white, 5’10” tall, weighed 180 pounds and had brown hair and hazel eyes. Both arms were heavily tattooed, the left having a large cupid double doll, and an eagle with a flag and the year 1959 inscribed under it. His right arm had his name Charlie in script letters and another eagle with a notation “Death Before Dishonor” under it. He lived in the Lower East Side in Manhattan at 205 Allen Street, in an area that was a hotbed of gang activity. Allen Street and the streets around it was where a Puerto Rican gang called the Forsyth Boys hung out. Even though Charlie was white, this did not cause him any problems and he hung out a candy store on Forsyth between Stanton and Ludlow Streets. Supposedly he was a member of the gang, although he denied it. At the minimum he would have known who the members of the Forsyth Boys were and would have most certainly been familiar with the gang lifestyle.

Charlie had a record for stealing a bicycle, breaking into parking meters, shoplifting from Macy’s department store, and disorderly conduct. He was also arrested for possession of not just a zip gun, but for stealing three rifles. He pilfered the rifles from a military cadet corps that he was a member of and where he practiced shooting at an armory in New Jersey. When it came to guns, Charlie just couldn’t help himself. He was obsessed with them and carried them “without any rhyme or reason.” When he was expelled from the University Settlement House, a spot where gangs and other youth from the Lower East Side liked to hang out, he returned and crashed a party while drunk and threatened everyone with a gun. He had to be subdued by guards.

In 1958 Charlie bought a .22 caliber rifle for $20 (a different one from the three rifles he had stolen from cadets), but unfortunately for him, his Mom discovered the gun. To make matters worse, his little brother found it on a couple of occasions and was caught playing with it, which infuriated his parents (understandably so). He had to get rid of it. But Charlie wasn’t about to obey his parents, so he used a hacksaw to saw off the barrel and the stock to make a sawed off rifle. This chicanery allowed him to hide the gun from his parents and little brother.

In February 1960, a boy who had originally lived in the Lower East Side and had moved to Williamsburg, made it known he wanted to buy a rifle. Charlie decided to sell his for $10. He met with some Puerto Rican boys on South Third Street in Williamsburg, and showed off the firearm, but a sharp-eyed policeman from the 92nd Precinct who was on foot patrol noticed the boys. Charlie spotted the policeman eyeing him while he was standing on the corner and so he ducked into a hallway at 363 South Third Street to escape his attention. The policeman saw that Charlie, who was a stranger in the neighborhood, had something hidden under his jacket.

When the patrolman entered the hallway, several of the Puerto Rican youths ran out a rear hallway entrance. He cornered Charlie and searched him after a brief struggle to escape. The sawed-off .22 caliber long rifle with one shell in the chamber and four in an attached clip was found inside Charlie’s right pants leg.

Charlie admitted to the police he was trying to sell the rifle for $10, and although the gang name of the boys he was trying to sell it to wasn’t in the report, this was in the epicenter of Phantom Lord turf, an exceptionally active gang from Williamsburg. In all probability he was trying to sell the rifle to the Phantom Lords who, according to their prior reputation, wouldn’t hesitate to use it on enemy gangs in the area, namely the Puerto Rican Hell Burners or the Italian Jackson Gents.

—

On February 23, 2018, my book on the Mau Maus and Sand Street Angels, who were two Brooklyn youth gangs from the 1950s, has been completed. It took 15 years of research and writing to complete Brooklyn Rumble: Mau Maus, Sand Street Angels, and the End of an Era. This book is roughly 6″x9″ and has 370 pages and includes a look at the characters in the Mau Maus and the details of a gang killing that happened in February 1959 in front of the iconic Brooklyn Paramount Theater (now Long Island University). If you want to buy a copy, click here and this link will take you to an online ordering page.